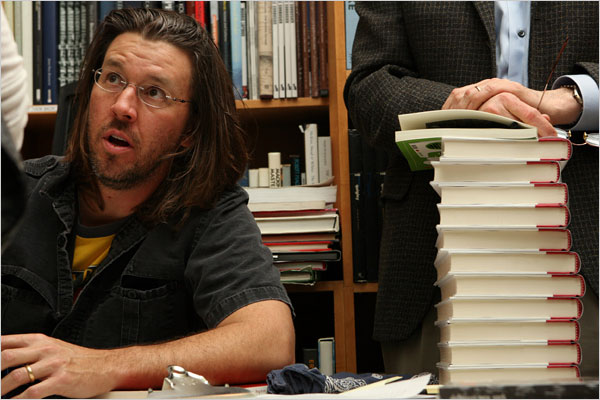

David Foster Wallace is a great writer. If you’re not familiar with him, he’s written extensively about tennis, and many brilliant essays on various topics for major magazines. An English professor at several colleges, he’s also written several novels, including Infinite Jest, which is the subject of this cranky post.

Brilliant but troubled, David Foster Wallace killed himself in 2008 at age 46.

I was first introduced to his writing in, of all places, Premiere, a now-defunct magazine about movies. His article covering a porn industry convention not only stood out in that fairly conventional magazine, it made my writer-brain sort of explode. The style was like nothing I’d ever read: show-offy vocabulary, intricate sentences, outlandish wit, deep perception. Years later I discovered the essay that put him on the map, so to speak: his account of his experience aboard a cruise ship (A Supposedly Fun Thing I Will Never Do Again).

I was hooked. I read many, not all, of his essays, including his pieces on tennis. As a formerly ranked junior tennis player, it was a subject of keen interest to him,

A few years ago, my son read Infinite Jest, and I was intrigued to try it. Not a small decision. It is some 1100 pages long, and is famously challenging in the manner of Pynchon, Beckett, Joyce. Those guys. Those difficult, opaque guys.

But I do enjoy tackling difficult books. Hell, the previous year I read Moby Dick. Every word, and I was really walloped by it.

So I picked up Infinite Jest. And I finished it. (Many people do not.) It took me six months.

My reluctant, humble conclusion: DFW the journalist is a towering figure. DFW the novelist: yeesh.

Jason Rhode articulated it beautifully in Paste Magazine:

“DFW is probably at his best in his journalism, in which he has to confront the outside world and people who are not creations of his mind. In Infinite Jest, it’s pure uncut DFW—just like Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, and off-putting for the same reason. Here’s a guy telling you how self-conscious he is about how self-conscious he is about how self-conscious he is about being smart, all while writing in a way guaranteed to get across just how smart and educated and self-conscious he is.”

I’m reluctant to diagnose DFW that way, but I will say this about Infinite Jest. The dense prose, the avalanche of unfamiliar words and indecipherable passages made it impossible to read for long periods. Brilliant sequences were followed by endless who-knows-what. Overall, it was a slog. For me.

More important, though, is that, despite its length, it rarely-to-never gave me what I most treasure about reading great fiction: the experience of being moved beyond words. A passage that makes me want to read it five times more (other than to learn what the hell it’s saying). Description that is so accurate or beautiful it gives me chills. An insight that offers a glimpse of something just out of reach, or a lightning strike of recognition. Presenting a character that gives me the sense I know that person. A perception of people, of life in general, of science or nature – of existence itself — that had never occurred to me before.

It perhaps wasn’t his intention to do so. He crafted a novel designed to work on another plane.

It didn’t work for me. Granted, DFW can write some startling prose. I did find it hilarious in parts. Certain characters, Pemulis being one example, emerged vividly even as they were presented cryptically, indirectly. This book’s depiction of addiction – from falling into it, to drowning in it, to striving to recover from it – was brilliant.

But the book needed an editor, despite what Wallace and the book’s editor contended at the time of its publication.

Now, this is a novel that received extravagant praise from many mainstream critics. Masterpiece, one of the great novels of all time, that sort of thing. Lofty praise from brainiacs can intimidate. So I’ve been reading about the book, reading lofty reviews of it, and visiting online forums to gather readers’ thoughts on it.

The smart reviews make me shrug; they don’t move the needle, but they do point out aspects I hadn’t considered. (The first chapter is actually the last chapter, duh!) And the online forums often make me wince – of course! No surprise. There are many smart, considerate exchanges, but wayyy too many in which critics and fans take the opposing view as a scalding condemnation of them, personally. Fans of the book are dupes, poseurs, sheep. Critics of the book are basically Neanderthals: illiterate, lazy, dim. Unworthy. Oh, the mud that is thrown!

I’m glad I read it. I was ecstatic when I finally finished it. My love for David Foster-Wallace, my sorrow at his suicide, is undimmed.

Now where did I put that copy of Premiere?